Fixture congestion and injuries in Football. The case of Harry Soutar.

Harry Soutar, the Australia and Sheffield United centre back has ruptured his achilles. Was fixture congestion to blame?

Earlier this year I wrote about ‘Away Days’ and how national team coaches are meeting the challenge of preparing professional football players in a heavily congested fixture calendar. The example I used was the Socceroos and the six games they contested in September, October and November 2024. Their European based players clocked up more than 100,000 km, crossed multiple time zones, and competed in climates markedly different to the countries they had traveled from. One of those players is Harry Soutar, the Socceroo and Sheffield United centre back who ruptured his achilles in the final moments of a game against Burnley on the 26th December. Soutar is on loan from Leicester City and will now face up to twelve months on the sidelines.

Getting injured is an occupational hazard for Footballers and one that all players must manage at some point. Some injuries are unavoidable, those that happen as a result of contact with another player or an insidious incident in which an ankle twists on the ground or where a player falls awkwardly. Others such as non-contact soft tissue injuries can be reduced. Having watched the footage of Soutar’s injury it would appear to fall into this category. It happened as he accelerated from an almost stationary position to challenge for a loose ball with no contact from an opponent, a classic mechanism for rupturing of the achilles.

Over the past two decades clubs have worked hard to reduce the prevalence of non-contact, soft tissue injuries. The most impactful strategy being an improved understanding and quantification of load management. On a daily basis club staff will collect data including movement characteristics from GPS devices (how far and fast the players have run during training), haematology (blood borne markers of muscle damage and oxidative stress), range of movement (is the movement in any of their muscles and/or joints compromised) and subjective wellness (how does the player feel and how have they slept) to determine how well individual players are coping with the load they are experiencing. Clubs use sophisticated software and algorithms to track these metrics and highlight which players are at most risk of injury so that their load can be modified accordingly. With such advances in this area, why didn’t it help Soutar? Likely because a significant contributor to the load players experience is the number of games they play, something clubs have far less control over than training.

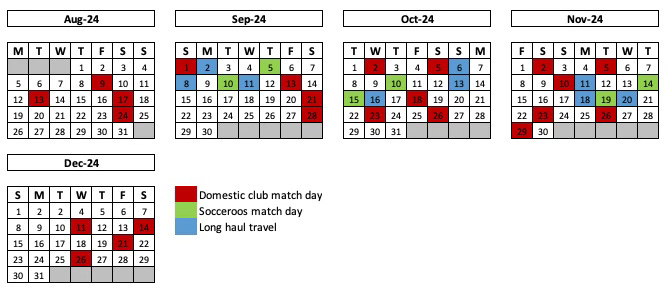

Since the start of the 2024/25 season Soutar has played in 29 games for club and county, 21 of these would be described as being in a back to back format characterised by less than 5 days recovery between consecutive matches. FIFPro has suggested games played in this format represent a heightened risk of injury. In addition to this congested fixture schedule Soutar travelled more than 100,000km for international fixtures between September and November. It is hard to argue this is representative of an environment that allows players to prepare and perform at their best, nor that such demands are likely to have contributed, in some part at least, to his injury. I have detailed Soutar’s fixtures since the start of the 2024/25 season in the chart below.

A counterargument may posit that clubs and coaches are not obliged to select players for every scheduled game. In fact, the reason they have such large squads (and they do) is so they can rotate players and limit exposure to excessive playing minutes. Indeed, more reciprocity between club and country may have seen Soutar rested for one of the international windows or omitted from club games scheduled immediately after returning from national team duty. Note that in the above chart Soutar played in all six games for the Socceroos and in the three club games that followed the international window, each was preceded by long haul travel over multiple time zones. Neither coach, however, is incentivised to do this. Both want their best players available for every game such is the pressure to win and the short tenure for coaches that cannot deliver almost immediate success. By my count 23 coaches have received their marching orders in England this season with the shortest tenure being only 100 days. Many of those reading may have been asked in an interview, ‘what will you achieve in your first 100 days in the new role’? For Football managers the answer may be ‘to still have a job!’ In such an environment there is little value in coaches resting players so that their performance is maintained later in the season. When players are available for selection, rested and ready to perform at their best, the coach may be already looking for a new job.

Players, meanwhile, are caught in the middle. Had Soutar suffered a head knock in any one of those games he would have been automatically ruled out for six days, longer if medics suspected a concussion had been sustained. No such mandated powers exist for medical staff to limit exposure to congested fixture schedules nor long haul travel despite both bringing with them a heightened risk of injury. We have developed, it seems, a form of cognitive dissonance. When presented with one risk, concussion as an example, we employ a sensible approach to limit harm that is mandated by FIFA and governing bodies. For others, say the heightened risk of injury that comes with fixture congestion, we are happy to ‘play on’. Both scenarios can have significant and long term negative health consequences for players. The game offers protection from only one of them.

With international competitions expanding and the new format for the Club World Cup being introduced in 2025 governing bodies in Football have to do more to protect players. FIFPro are doing an excellent job in advocating for change however it has to come quicker. This might be in the form of a maximum number of back to back games that players can take part in each season, minimum recovery time after long haul travel, a maximum number of games per season, or mandated rest periods during and at the end of the season. Without such mandates it is hard to see a resolution coming from individual clubs or national teams.

Football’s competitive formats are growing to satisfy our appetite for competitions that pitch the best against the best and capitalise on a seemingly ever expanding consumer market. If we cannot do this in a way that constrains the growth in matches, we may find that the best of the best are no longer available for selection.